What are migraines:

Your History:

Describing the headaches:

- age at onset

- warning signals (prodrome or aura)

- location of the pain

- character of the pain

- tempo of pain progression

- time to peak intensity

- circadian pattern (eg, awakening the patient from sleep at a particular time, present upon awakening, occurring at specific times during the day)

- associated symptoms

- aggravating or relieving factors

- how they feel after the pain resolves

- how the headache affects their ability to function.

- Besides knowing about the bad times, ask about the good times: “How often are you completely headache free?”

Do you get any warning that you are getting a headache before the pain starts?

Prodrome may occur up to 48 hours before the onset of migraine pain. Patients may not even realize that they experience prodrome symptoms or that they are related to migraine; prodromal symptoms are often misinterpreted as triggers.Ask specific questions, querying about uncontrollable yawning, change in mood, tiredness, cognitive dysfunction, food cravings, excessive thirst or urination, or neck pain.When the associated symptoms of migraine (ie, nausea, photophobia, and osmophobia) begin before the onset of aura or headache, they are considered prodromal.

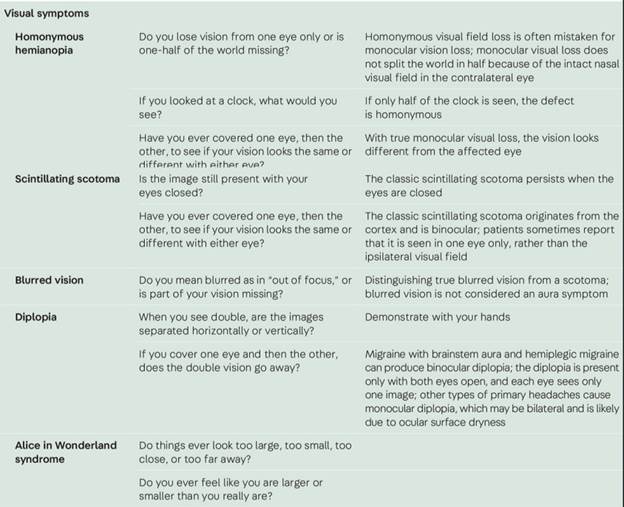

Aura is a transient symptom arising from the brain that typically precedes the headache but may occur during the headache phase, after the headache, or as an isolated event.Aura transpires in approximately 30% of patients with migraine and occasionally occurs with cluster headache. Typical aura is visual, somatosensory, or affects speech and language, lasting 5 to 60 minutes. Manifestations of aura include flashing lights, shimmering zigzag lines with or without an enclosed area of scotoma, sparkles, dots, homonymous hemianopia, tunnel vision, visual distortion (metamorphopsia), transient visual loss, other vision problems, aphasia (typically expressive), numbness, paresthesia, phantosmia, auditory hallucinations, weakness, imbalance, vertigo, diplopia, altered levels of consciousness, Alice in Wonderland syndrome (ie, an alteration of visual perception characterized by distorted body images, external environment, or both), and other neurologic symptoms.

How your head pain starts. Where is it located at first? Does it spread or travel?

Migraine often starts in the neck and spreads anteriorly. Alternatively, it may start on one side of the head, around the eye or sinus area. Sometimes it begins on one side and later moves to the contralateral side of the head or becomes bilateral. While the diagnostic criteria for migraine include unilaterality, about 40% of adults and most children have bilateral head pain. Unlike other types of headaches, the location may vary from attack to attack in an individual.

The trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias are almost always centered around one eye. Cluster headache pain may be orbital or retro-orbital, involving the ipsilateral temple, forehead, jaw, or face. Patients will often point to the specific area of pain. Tension-type headache is nearly always bilateral, sometimes bandlike, but need not involve the entire head. Patients with nummular headache outline a well-circumscribed round or oval area on the head to localize the pain.

If the headache is unilateral, ask the patient, “Are your headaches always on the same side of your head?” The head pain in individuals with unilateral migraine pain commonly occurs on either side of the head unpredictably, but some people have attacks that always occur on the same side of the head. During a bout of cluster headache and with the other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, the pain is side-locked, always occurring on the same side. Hemicrania continua is side-locked by definition, although the pain may not encompass the entire side of the head. A de novo side-locked headache may signal a secondary headache disorder such as a structural intracranial process, giant cell arteritis, or a CSF pressure disorder.

How would you describe the pain? What does it feel like?

Prompting is sometimes required for this question, such as throbbing, pounding, sharp, stabbing, shooting, aching, pressurelike, or burning. Throbbing, pounding pain is characteristic of migraine. However, migraine pain may be steady, aching, or stabbing.Tension-type headache is pressurelike, aching, or squeezing, like wearing a hat or headband that is too tight.Cluster headache is described as stabbing, boring, hot poker, knifelike, or drilling, “like someone stuck an ice pick in my eye.”

How severe is the pain when it starts and how severe does it get? How long does it take for the pain to reach peak intensity?

The intensity questions are helpful for diagnosis and treatment. Migraine characteristically starts with mild pain that gradually builds in intensity. The time to peak intensity is quite variable and this aspect of pain development is extremely important when selecting an acute treatment strategy. If the pain crescendos over hours, oral acute therapies are the preferred option as there is enough time for systemic absorption if they are taken early in the episode. Patients experiencing pain that peaks in intensity within 30 minutes may require nonoral acute treatment if rapidly acting oral treatment is ineffective.

Cluster headache and episodic and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania typically peak in intensity within several minutes.21 Hence, there is not enough time for oral agents to take effect, and other routes of administration are employed such as inhalation (oxygen for cluster headache), subcutaneous injection, and intranasal delivery.

The pain intensity of migraine varies but is generally moderate to severe, compared with mild to moderate pain in tension-type headache. Severe to very severe pain characterizes cluster headache and paroxysmal hemicrania; most patients indicate that it is the worst pain they have ever experienced and some patients report suicidal ideation during an attack.22

Pain that starts instantly at peak intensity is called thunderclap headache.23 While thunderclap headache may be a primary headache disorder, it raises concern for a secondary headache, particularly as a new-onset headache. Conditions producing thunderclap headache include reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, and spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Thus, primary thunderclap headache is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring brain and cerebrovascular imaging.

Do your headaches occur at any particular time of the day or night? Do they awaken you from sleep? Are they present upon awakening?

Headaches that awaken the patient from sleep need to be distinguished from waking up during the night for other reasons and noticing that the headache is present. Some patients have a hard time discerning the difference. If the patient has nocturnal awakening or wakes up in the morning with a headache, it is helpful to note the severity of the pain, whether it has already peaked in intensity, and if other symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, tearing, rhinorrhea) are present at the time.

These questions assist in both diagnosis and treatment. Recurrent episodes of nocturnal awakening can be a symptom of secondary headaches, particularly sleep disorders, acute medication overuse (when the medication wears off during sleep), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nocturnal hypertension, or brain tumors. However, nocturnal awakening also occurs in primary headache disorders including migraine, cluster headache, hypnic headache, and paroxysmal hemicrania.Circadian periodicity is a feature of cluster headache.Migraine may also display a circadian preference as the most common time to experience migraine is upon waking up in the morning.

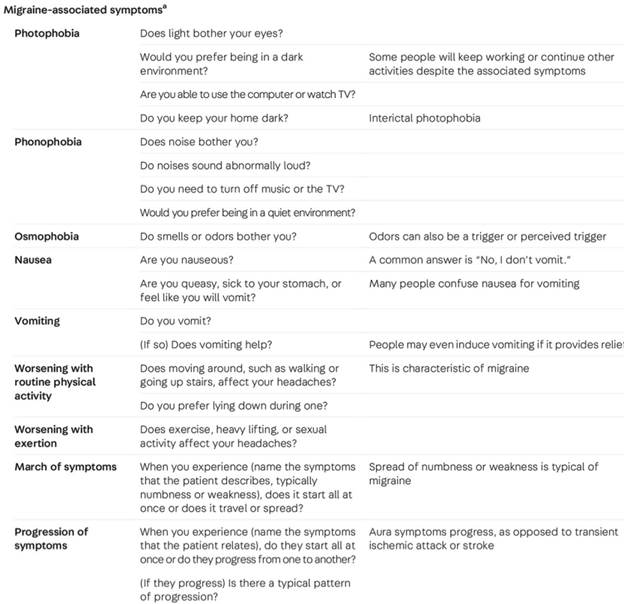

Are there other symptoms of a primary headache disorder?

The associated symptoms of various types of headache conditions sometimes lead to greater impairment than the head pain (referred to as most bothersome symptoms). Photophobia is the most common associated symptom in the United States.

Although trigeminal autonomic symptoms suggest a trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, they may also occur in migraine. Their presence in migraine is often less pronounced (eg, slight watering of the eyes rather than tears streaming down the face) than with the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias and are most often bilateral.Headaches accompanied by nasal congestion or rhinorrhea may be incorrectly interpreted as sinus related; such headaches are usually either migraine or cluster headache.

Others include phonophobia, osmophobia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, aura symptoms during the headache, and the following trigeminal autonomic features:

What do you prefer to do (physically) during an attack?

Even if the patient cannot lie down because of situational circumstances, do they prefer lying down, sitting, pacing, or moving? If recumbent, can they lie motionless, or are they unable to get comfortable due to thrashing, tossing, or turning.? If they sit, do they sit quietly or rock back and forth in the chair? Is there a change in demeanor such as agitation?

One of the most diagnostically helpful characteristics of migraine is worsening with activity, and the overwhelming majority of patients with migraine prefer to lie down motionless in a dark, quiet environment. However, circumstances often dictate or constrain a patient’s physical response to a headache attack. In contrast, patients with cluster headache rarely prefer being motionless and experience restlessness or agitation.They may pace, rock back and forth, toss, turn, or thrash in bed (eg, “Are you able to lie still, or do you thrash in bed?”), or inflict bodily injury on themselves for distraction, such as banging their head or body parts against the wall or digging their fingernails into their skin. Vocalization during a cluster attack may occur, including yelling or screaming.

Is your skin sensitive to touch during the headache?

Cutaneous allodynia is the experience of pain or discomfort with a stimulus that is not ordinarily painful, such as touching the skin. About 60% of patients with migraine report that their hair hurts, they cannot brush their hair or put it in a ponytail, they need to take off jewelry or clothing, they are unable to tolerate taking a shower or the weight of the sheets or blankets touching them, and they do not want anyone else to touch them during a migraine.

Cutaneous allodynia is a feature of the central sensitization of second-order (cephalic sensitization) and third-order (somatic sensitization) nociceptive trigeminal nucleus caudalis neurons. During central sensitization, the threshold for noxious stimuli to produce pain decreases and the nervous system is in a heightened state of reactivity, causing a sensation of pain in response to stimuli that are normally not pain provoking. Central sensitization is also associated with the development and sustainment of chronic pain.

How long does the severe pain last?

The headache diagnosis is often defined by its duration, particularly for the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Cluster headaches last 15 to 180 minutes when untreated or unsuccessfully treated, but some patients experience milder pain in between the severe attacks; the duration of the severe pain is the defining characteristic. While the severe pain of migraine is the most disabling, patients often have lingering pain lasting up to a day afterward.

Questions such as “How do you feel after the pain is over?” and “How long does it take to feel ‘back to normal’?” allude to the postdrome, which is a common feature of migraine, otherwise known as the migraine “hangover.” There may be mild residual pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”), hunger, gastrointestinal symptoms, sensory sensitivity, or vertigo lasting up to 1 to 2 days. Note that this is part of the migraine attack and should be considered when determining the number of migraine days in a given period. Effects or side effects of acute medications may cause similar symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish the etiology in some patients; however, postdrome symptoms are most frequently incorrectly attributed to medications. For patients who are rarely or never headache free, it is important to ask how long it takes to return to their baseline state.

Do you have symptoms between attacks (eg, pain, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia)?

Although we tend to concentrate on headache attacks when taking a history, symptoms can persist into the interictal phase, particularly in migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache. Several lines of evidence document that patients with episodic and chronic migraine have a poorer quality of life in between episodes compared with those without migraine.37

Functional imaging studies corroborate changes in the brain during this interictal phase. In addition to the aforementioned symptoms, the interictal burden of migraine is associated with photophobia, anxiety (fear of the next attack), depression (inability to make plans because of the possibility of having a migraine episode), motion sickness, fear of upcoming events, stigma (reluctance to tell others about their headaches), and worse interpersonal interactions with others. Individuals experiencing interictal impact from migraine report having to alter their lifestyle to avoid triggers or in response to an impending attack. Furthermore, migraine affects work, career, daily activities, relationships, and even the decision to have children. Preventive migraine treatment benefits patients experiencing interictal burden.

How many days in one month are you completely headache free and “clear headed”?

People tend to report their worst headaches but may have other, milder headaches that they “live with” and can continue functioning through. Neglecting to ask about pain freedom in addition to pain days may lead to an incorrect diagnosis.

Have you identified anything that triggers your headaches?

The concept of migraine triggers is controversial, as some presumed triggers may actually be premonitory symptoms (eg, food cravings, bright lights, loud noise, neck pain). Classifying one exposure followed by a migraine episode as a trigger is insufficient, as a pattern of cause and effect must be established. That said, many individuals with migraine relate that exposure to a trigger does not result in a migraine 100% of the time. One observational study using a smartphone app showed that, except for neck pain, even the most frequently reported triggers were present in fewer than one-third of individuals reporting them. Commonly perceived triggers include odors (eg, volatile substances, fragrances, smoke), stress (during or following a migraine attack), weather (eg, heat, sferics [atmospheric electromagnetic impulses resulting from lightning]), missing meals or hypoglycemia, changes in sleep pattern, dehydration, menses, alcohol, caffeine, and various foods (eg, aged cheese and other aged foods, monosodium glutamate). Headache is a side effect of many medications, including medications used to treat headache, which also needs to be considered.

When patients identify a reproducible trigger, avoiding it is helpful. However, if the suspected trigger is actually a premonitory symptom, the patient may be restricting their exposure unnecessarily. One example of this is chocolate, which may be consumed as a prodromal food craving when the headache occurs regardless of what one eats. Thus, identifying true triggers helps mitigate exposure, but incorrect trigger attribution leads to hypervigilance that affects quality of life.

Medical history

The medical history yields clues for diagnosing migraine if the patient experienced infantile colic, torticollis, unexplained abdominal pain, vomiting or vertigo, or motion sickness in childhood. Changes in headache patterns related to menses, pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause frequently occur in people with migraine. A history of cancer or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) raises the possibility of a secondary headache.

The general medical history helps guide treatment, as some medications are either contraindicated or ill-advised in patients with certain medical problems. Examples include triptans in patients with coronary artery disease, tricyclic antidepressants in patients who are prone to constipation, and topiramate in patients with a history of calcium phosphate kidney stones. Certain conditions are associated with primary or secondary headaches, including thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and joint hypermobility disorders.

Social history

A standard social history reveals information about smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use, employment type and status, physical activity, and the home environment. It is particularly important to ask about current or previous physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Migraine and tension-type headache are more prevalent in individuals with recalled childhood maltreatment, particularly in sexual and gender minority adults, often associated with coexisting anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Adverse childhood experiences are risk factors for migraine and other headaches in adults, as well as the progression from episodic to chronic migraine.

Alcohol often triggers headaches, specifically migraine and cluster headache. Patients with cluster headache are more likely to smoke or have been exposed to secondhand smoke than the general population, although there is no evidence that smoking cessation improves the headaches.Certain stressors at home or work may be identified that contribute to the headache burden.

Current and previous medications

In addition to current medications, obtain a list of drugs that the patient has tried in the past for headache treatment, including the strength, frequency, duration of action, effect, and side effects.

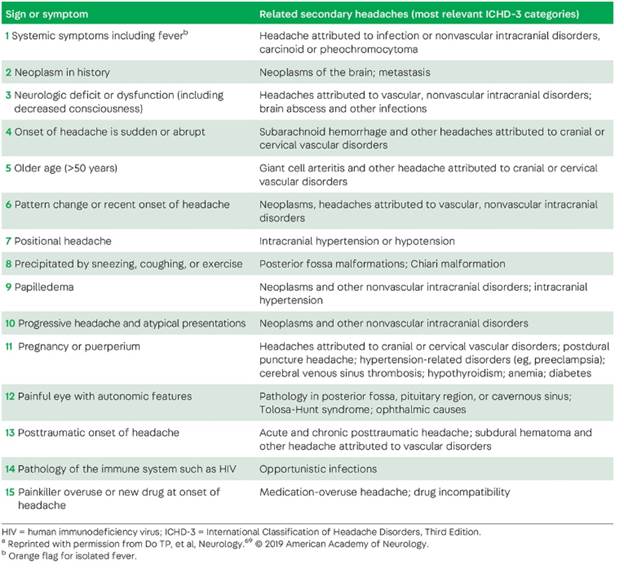

Assessing For Secondary Headache Disorders

Keeping the possibility of a secondary headache in mind while taking the history.

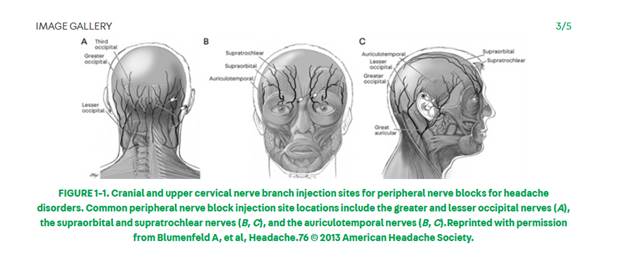

Exam

- Tenderpoints: Palpation of cranial peripheral sensory nerves for tenderness or pain reproduction including the greater and lesser occipital nerves, auriculotemporal nerves, supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, zygomaticotemporal nerves, and the trochleae.

- Neck – palpation for tenderness

- Assessment of jaw opening distance, crepitus, tenderness

Acute Treatment of Migraine

Universal principles can increase the chances of a positive response:

- Treat early, when pain tends to still be mild

- Match medication type to attack severity

- Use the maximum dose4

- Consider nonoral formulations

- Use combination treatments

- Treat nausea

Simple analgesics

For nonincapacitating attacks, acetaminophen 1000 mg was associated with higher rates of pain relief and pain freedom at 2 and 6 hours and greater reduction in disability and most bothersome associated symptoms compared with placebo. Acetaminophen is associated with hepatotoxicity at higher doses.

Many combination analgesics contain acetaminophen and patients should be educated to consider the total daily dose across medication types. Acetaminophen is generally well tolerated.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Over-the-counter NSAIDs have demonstrated benefit for migraine in multiple clinical trials. Aspirin 500 mg to 1000 mg orally, ibuprofen 400 mg orally, and naproxen 500 mg to 550 mg orally all have at least two positive randomized controlled trials showing improved pain reduction or relief at 2 hours compared with placebo (Level A evidence). Level A evidence also supports diclofenac 50 mg to 100 mg orally and celecoxib 25 mg/mL oral solution. The new formulation of celecoxib, a 25 mg/mL oral solution, was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved specifically for acute migraine treatment in 2020 with a recommended dose of 120 mg. NSAIDs with Level B evidence include ketoprofen 100 mg orally and ketorolac 30 mg to 60 mg IM or IV.

Adverse effects of NSAIDs include gastric irritation and increased risk of gastric bleeding, which are more common with frequent use. Patients who take NSAIDs frequently for migraine should be monitored for the development of gastrointestinal symptoms. NSAIDs should not be taken by people with renal dysfunction. As a class, NSAIDs increase the risk of cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, so cardiac risk factors should be considered in patients who may use NSAIDs frequently.

Combination analgesics

The over-the-counter combination of aspirin 500 mg, acetaminophen 500 mg, and caffeine 130 mg is established as effective (Level A evidence) for acute migraine treatment per the AHS acute treatment evidence review.

Combinations of butalbital and caffeine with either aspirin or acetaminophen, available by prescription, received Level C evidence (possibly effective). Frequent but inconsistent use of caffeine may cause a withdrawal phenomenon.

A combined formulation of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine is best for patients with milder infrequent attacks and using this combination more than 8 times monthly should be discouraged.

Butalbital combination medications should not be used as acute migraine treatment under most circumstances given poor evidence for efficacy and risk of worsening headache burden. Patients who use this combination should be monitored carefully for increases in attack frequency.

Migraine-Specific Treatments

Triptans – there are 7

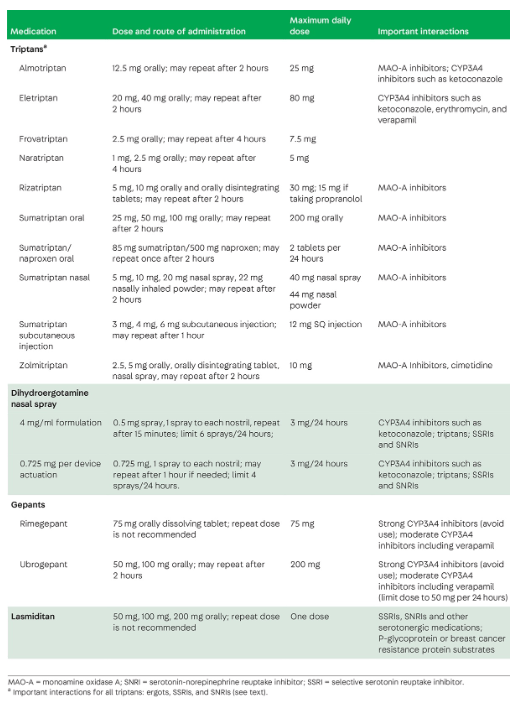

Triptans are the mainstay of migraine-specific acute treatment and are usually the first prescription acute treatment offered. All seven triptans are available as oral tablets. Rizatriptan and zolmitriptan are available as orally dissolving tablets, sumatriptan and zolmitriptan as nasal sprays, and sumatriptan as a subcutaneous injection.

A 2015 network meta-analysis of triptan studies found that the most effective triptans produced pain freedom 37% to 50% of the time, compared with 11% in the placebo group. This study also found that subcutaneous sumatriptan, rizatriptan and zolmitriptan orally disintegrating tablets, and eletriptan tablets were the most effective formulations.

Triptans differ primarily in pharmacokinetics.

- The long half-lives of naratriptan and frovatriptan may reduce recurrence, making these good options for patients with long-duration attacks or who have recurrence after initially successful treatment. They may also be given twice daily for the management of migraine associated with menses.

- Patients who require fast-acting acute treatment may do best with sumatriptan nasal spray or subcutaneous injection, zolmitriptan nasal spray, or rizatriptan orally disintegrating tablets.

Triptans are generally well tolerated but a small percentage of patients may experience triptan sensations (ie, facial flushing, heat, or pressure). Patients should be counseled at the time of prescription about the possibility of triptan sensations and reassured that such sensations do not indicate an allergic reaction. Triptans are contraindicated in patients with a history of coronary heart disease or coronary vasospasm. Current practice is to exercise caution in patients with multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease. Other contraindications include a history of ischemic stroke and poorly controlled hypertension. Triptans have historically been avoided in patients with hemiplegic migraine or migraine with brainstem aura due to concern for increased stroke risk.

Concurrent use of triptans and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) has historically been contraindicated due to concern for serotonin syndrome. Based on the available evidence, it may be appropriate to prescribe triptans in patients taking SSRIs or SNRIs and to provide education about serotonin syndrome at the time of prescription.

Dihydroergotamine – a rescue treatment

In the outpatient setting, DHE is primarily available as a nasal spray.29 Two formulations are available: one with a 4 mg/ml solution administering 0.5 mg per spray and another with 0.725 mg per spray. The dosing regimen is different depending on the formulation. DHE can cause significant nausea, which often limits tolerability. Frequent or long-term use of ergot derivatives has been associated with retroperitoneal and pleural fibrosis. Due to these limitations, DHE is more often used as a rescue treatment rather than initial therapy for migraine attacks. It may be considered in patients who have not responded to first-line or second-line acute treatments. It is also particularly helpful as a rescue treatment and in the inpatient setting.

DHE is contraindicated in patients with coronary artery disease, vascular risk factors, peripheral vascular disease, poorly controlled hypertension, or who are taking other vasoconstrictors. DHE should not be used in the same 24-hour period as a triptan.

Gepants

Rimegepant (Ubrelvy) and ubrogepant (Nurtec) are small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists, also known as gepants. Both are FDA approved for acute treatment of migraine, with efficacy supported by multiple randomized controlled trials. In phase 3 clinical trials of ubrogepant 100 mg or rimegepant 75 mg, 19% to 21% of participants in the active arm experienced pain freedom at 2 hours compared with 9% to 10% in the placebo group, and 35% to 37% showed relief of the most bothersome symptom in the active group compared with 9% to 10% in the placebo group. Ubrogepant may be repeated once after 2 hours, while rimegepant should not be repeated.

Ubrogepant and rimegepant were very well tolerated in clinical trials. The most commonly reported adverse events were dry mouth, nausea, and somnolence, all occurring in less than 4% of the trial population. Ubrogepant should be avoided in patients taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors and the dose should be limited to 50 mg in patients taking verapamil.

Evidence to date suggests that gepants do not cause vasoconstriction or increase the risk of cardiac events and are therefore good alternatives for patients with cardiac disease or vascular risk factors. Gepants are also thought not to contribute to medication-overuse headache. Rimegepant is approved for preventive treatment of migraine with every-other-day dosing. Gepants may be particularly helpful in patients with medication-overuse headache.

Lasmiditan (Reyvow)

Like triptans, lasmiditan is a serotonin receptor agonist. Lasmiditan has a high affinity for the 5-HT1F receptor, which provides similar antinociceptive effects as triptans but without the vasoconstrictive potential. In phase 3 trials of lasmiditan 100 mg, 28% to 31% of participants reported pain freedom at 2 hours, and 42% to 44% reported freedom from their most bothersome symptom at 2 hours, versus 10% to 13% for both endpoints in the placebo groups.31

The side-effect burden of lasmiditan is higher than that for triptans and gepants, with 13% to 18% of participants in the lasmiditan 100 mg arm experiencing dizziness compared with 2% to 3% in the placebo arm. Somnolence, fatigue, nausea, and paresthesia were also experienced by 3% to 6% of patients in the active arm versus 1% to 2% in the placebo arm. Safety evaluations showed that driving was impaired after lasmiditan use at all doses, and patients reported more sedation at 8 hours after lasmiditan use compared with placebo.Patients should therefore be counseled to avoid any activity requiring alertness, including driving, for at least 8 hours after taking lasmiditan.

Lasmiditan is a good alternative to triptans in patients with vascular disease or vascular risk factors, especially if they have responded to triptans previously. It may be better tolerated at night due to the side effects of somnolence and the restrictions on activity after taking it.

Antiemetics

Several dopamine receptor antagonist antiemetics, including metoclopramide 10 mg orally and prochlorperazine 10 mg orally, are effective for the reduction of migraine pain and freedom from migraine pain at 2 hours. They may be good choices for patients who need a combination of acute treatments, especially when nausea is a prominent symptom. Promethazine and prochlorperazine can be sedating and may be especially helpful in patients who benefit from deep rest as part of their acute treatment plan. Antiemetics have not been associated with an increased risk of medication-overuse headache and metoclopramide monotherapy is sometimes used in this setting. Frequent use of metoclopramide and the phenothiazine antiemetics may cause extrapyramidal symptoms. Although ondansetron is an effective treatment for nausea and is not sedating, it does not have intrinsic antimigraine pain properties.

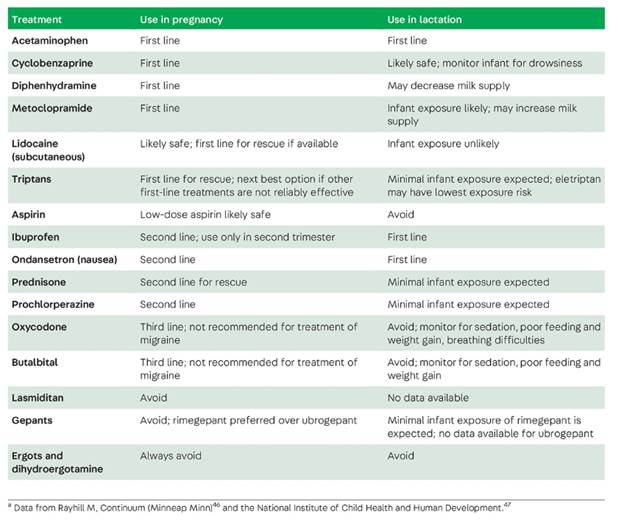

ACUTE TREATMENT DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

Rescue Treatment

Rescue therapy should be considered in any patient who has a rapid escalation of pain or attacks accompanied by severe nausea or vomiting, who sometimes have attacks that do not respond to typical treatment, or who have a history of emergency department visits for migraine for any reason. Nonoral treatments are necessary for patients with significant vomiting and typically have a faster onset than oral treatments.

The most effective nonoral migraine-specific treatment is subcutaneous sumatriptan. Subcutaneous sumatriptan can be used as a rescue 2 hours after shorter-acting triptans and 4 hours after longer-acting triptans if needed. The total triptan exposure should be limited to 2 doses per 24-hour period. The side effects of parenteral sumatriptan are similar to those of the oral formulation but are typically stronger and have a faster onset.

Triptans and DHE nasal sprays are another alternative. DHE nasal spray can be used 24 hours after a triptan dose, making it more useful for situations where the headache lingers into the following day and backup treatment is needed, or if a nontriptan medication is used as a first-line treatment. Pretreatment with an antiemetic is necessary. The NSAID indomethacin is also available as a 50 mg suppository and can be useful if triptans and DHE are contraindicated or not tolerated.

Many people with migraine find sleep therapeutic and sedating medications are helpful in this circumstance. The phenothiazine antiemetics promethazine and prochlorperazine typically cause sedation and are available as suppositories and may treat migraine pain as well. Other sedating medications, such as antihistamines, are sometimes used for similar reasons.

In-office treatments may include IM injections of ketorolac or occipital nerve blocks with lidocaine. Clinical trials support the use of IM injections of ketorolac as an acute treatment. Several positive trials have evaluated occipital nerve block as an acute treatment for migraine as well.

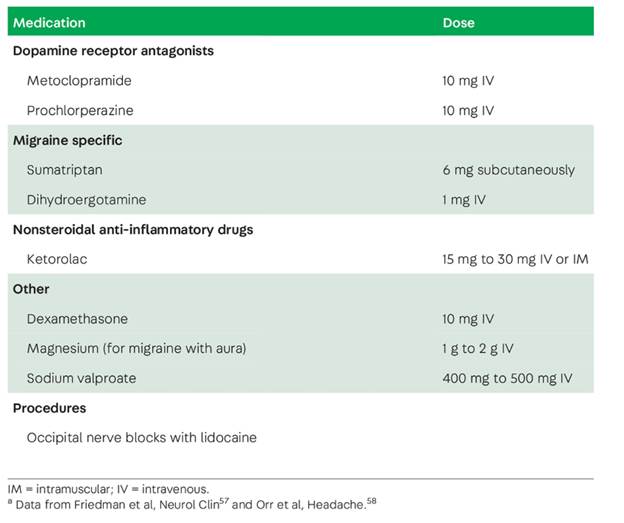

Acute Treatment in the Emergency Department and Inpatient Settings

The management of vomiting and rehydration are important first steps.

For the management of migraine pain, evidence supports IV metoclopramide and prochlorperazine, as well as subcutaneous sumatriptan.Corticosteroids, specifically dexamethasone, were shown in a meta-analysis to reduce the likelihood of headache recurrence in the days following an emergency department visit but did not reduce acute pain better than placebo.Although sodium valproate is effective compared with placebo and is sometimes used as a rescue treatment.

Opioid use should be avoided in the emergency department as opioids have lower evidence for effectiveness, are associated with medication-overuse headache and decreased subsequent responsiveness to acute treatment, and may reinforce emergency department use in patients seeking opioids.

Inpatient admission for the management of severe migraine may be necessary if adequate pain control is not achieved in the emergency department. Dihydroergotamine with metoclopramide IV every 8 hours is an effective but side effect–prone inpatient treatment approach. In addition to nausea, DHE IV can cause leg pain or cramping, chest discomfort, sedation, flushing, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, vasoconstriction, and hypertension.

Prevention of Migraine

the goals of preventive treatment include reducing the frequency, severity, duration, and disability associated with attacks, reducing the need for acute treatment and risk of medication overuse, enhancing self-efficacy and health-related quality of life, and reducing headache-related distress and interictal burden. Not everyone with migraine needs preventive treatment. As attack frequency and disability increase, the need for preventive treatment increases.

prevention should be considered if attacks interfere with daily activities despite optimized acute treatment and if attack frequency and disability exceed specified thresholds (table 4-112), in the setting of medication-overuse headache, or based on patient preference. For people with less than 6 monthly headache days, the choice to initiate treatment may be determined, in part, by the presence and extent of migraine-related disability. For people with 6 or more monthly migraine days, disability is usually not required for a recommendation to offer prevention.

Among the evidence-based options, the choice is often based on the patient’s comorbidities and potential adverse events. For patients with hypertension, a beta-blocker or candesartan are frequent choices. For patients with obesity, topiramate may promote weight loss and is a reasonable option. For patients with comorbid depression and insomnia, amitriptyline may be a preferred choice. For most migraine-nonspecific oral preventive medications, the best practice is to start at a low dose and gradually increase the dose based on tolerability and response. The most frequently cited reasons for discontinuing nonspecific oral preventive medications are insufficient efficacy, poor tolerability, or both.

After the failure of two classes of migraine-nonspecific preventive medication, consideration should be given to trying either onabotulinumtoxinA or a CGRP-targeted therapy.

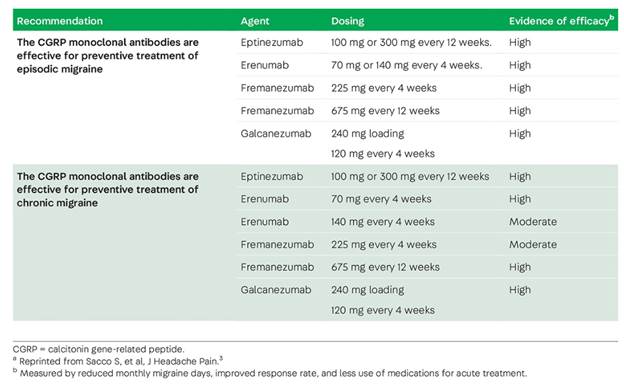

CGRP-TARGETED MIGRAINE PREVENTIVE MEDICATIONS

These agents are generally used in people who cannot tolerate or do not respond to at least two migraine-nonspecific preventive medications with established or probable efficacy.

Erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), and galcanezumab (Emgality) are administered as subcutaneous injections, while eptinezumab (Vypeti) is administered by IV infusion. Eptinezumab is given by IV infusion in doses of 100 mg or 300 mg every 3 months. Erenumab can be started as a 70-mg or 140-mg subcutaneous dose once monthly. Fremanezumab can be started as a 225-mg subcutaneous dose once monthly or 675 mg (3 225-mg injections) every 3 months. Galcanezumab is administered subcutaneously in a loading dose of 240 mg (2 120-mg injections) and then dosed at 120 mg once monthly. The three subcutaneous agents are prescribed with autoinjectors. Eptinezumab. The gepants atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec) have the advantage of oral dosing.

The CGRP monoclonal antibodies and the gepants are generally well tolerated. In clinical trials, the most commonly reported adverse events with the CGRP monoclonal antibodies are constipation and injection site reactions.The safety of CGRP monoclonal antibodies in pregnancy and lactation has not been demonstrated and these drugs should likely be avoided in these settings. The European Headache Federation recommends caution in patients who have vascular disease or risk factors and Raynaud phenomenon.The guideline also recommended that erenumab be used with caution in patients with a history of severe constipation.

Another factor to consider is pregnancy planning, as safety during pregnancy is not known. Because monoclonal antibodies have a 1-month half-life on average, 95% washout is achieved after 5 months, requiring a long washout period if a patient decides to become pregnant. Atogepant and rimegepant have 11-hour half-lives and are 95% eliminated in 55 hours, greatly reducing the washout period.

To ensure an adequate trial, CGRP-targeted preventive medications should be given for at least 6 months. When treatment is successful, a pause may be possible after 12 to 18 months of continuous therapy. For CGRP monoclonal antibodies, switching between antibody classes (ligand versus receptor) can be beneficial in some patients. Several small studies with rimegepant and ubrogepant support the concomitant use of CGRP monoclonal antibodies and gepants.

Longitudinal epidemiologic studies have shown that within individuals, migraine frequency can vary over time in a pattern referred to as the migraine roller coaster. Patients using rimegepant as an acute treatment sometimes transition to using rimegepant as a preventive treatment as headache frequency rises. Conversely, as headache frequency declines, they may transition back to acute treatment.

A second emerging paradigm is known as situational prevention, where patients treat during short-term periods of increased risk for migraine while completely asymptomatic .Situational prevention has been applied to the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine, Saturday morning headaches, and headaches associated with stress or travel.

A third novel paradigm involves treating patients during the prodrome, before headache begins, to prevent the onset of headache.

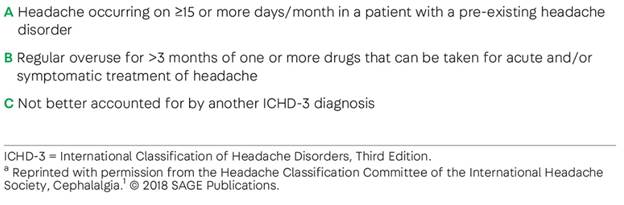

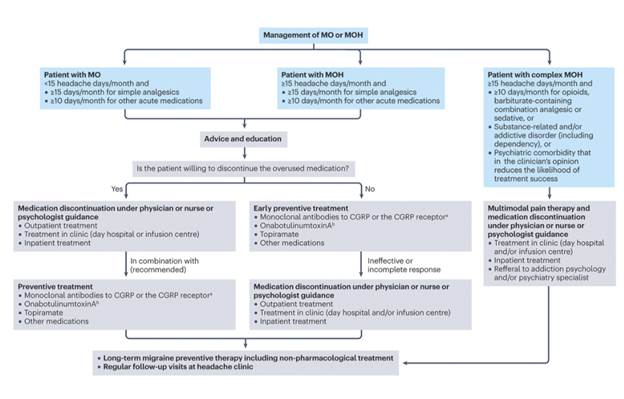

Medication-Overuse Headache

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Acute exacerbations may require additional treatment. If trigeminal neuralgia pain results in poor oral intake and dehydration, IV fluid resuscitation may be necessary. In addition, infusions of fosphenytoin and lidocaine are also reported to be useful.

More information on the utility of other medical approaches has come to light in recent years.

oral lacosamide

IV lacosamide was as effective as, and better tolerated than, IV fosphenytoin

onabotulinumtoxinA for both primary trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia due to MS, outcomes were favorable and similar for both types (effective for 45% of patients with primary trigeminal neuralgia and 52% of those with trigeminal neuralgia due to MS) and, regardless of etiology, those with concomitant continuous pain and no prior interventional procedures had a greater chance of improvement.27

Finally, there is conflicting evidence regarding erenumab. A retrospective analysis of 10 patients revealed a response in 90% after 6 months,28 but a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial failed to show a difference between erenumab and placebo after 4 weeks.29

Resources: https://mclarkgaspervic.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/educ-resource-migraine.jpeg

Pseudotumor Cerebri Syndrome and Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Pseudotumor cerebri syndrome encompasses all cases of intracranial hypertension without ventriculomegaly or a mass lesion. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is diagnosed when no secondary cause is identified.

The headache phenotype of increased intracranial pressure does not distinguish it from primary headaches; most individuals with IIH experience headaches that fit the description of either migraine without aura or tension-type headache. Headaches arising from IIH often respond to analgesics early in their course. The Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial found that more than 40% of participants, of whom 161 of 165 were women, had a prior history of migraine, more than twice the estimated prevalence in the general population of women. However, patients with IIH can generally distinguish their IIH-related headaches from their previous migraine attacks.

Transient obscurations of vision and pulsatile tinnitus are common symptoms of IIH. Transient obscurations of vision generally last seconds to a minute with either complete or partial loss of vision in one or both eyes. They are often provoked by arising after bending over. The new onset of pulsatile or nonpulsatile tinnitus coinciding with the onset of headache also suggests intracranial hypertension.Patients frequently do not volunteer the auditory symptoms, so direct questioning is imperative.

Although positional headache occurs with IIH, patients with IIH rarely report rapid changes in headache severity with positional changes. The headache may be worse in the morning, as intracranial pressure increases after prolonged recumbence.

IIH affects people of childbearing age with obesity, but pseudotumor cerebri syndrome does not share the same predilection due to the various causative etiologies. Thus, suspected patients should also be queried regarding the use of tetracycline and its derivatives (eg, doxycycline, minocycline), vitamin A and retinoids (eg, all-trans retinoid acid, isotretinoin), and lithium.