This paper is a detailed description of the pathophysiology of concussion followed by a rationale for vitamin and mineral supplements. Metabolic injury directly related to the immediate post-concussion hyperactivity in the brain is described. Hyperactivity has 2 effects: (1) depleting the brain of important vitamins that support a key cellular enzyme, Pyruvate Dehydrogenase, and (2) setting the stage for free radical damage to the mitochondria.

A key concept is that Pyruvate Dehydrogenase is largely supported by B vitamins, including Thiamine (vitamin B1), Riboflavin (B2), Niacinamide (B3), Pantethoic acid. Of these, Thiamine is particularly vulnerable to hypermetabolism due to limited body stores and its key role in supporting cellular metabolism overall. There are numerous examples of clinical situations analogous to concussion in which the result is Thiamine depletion with subsequent impaired metabolism. These situations are described below and include Wernicke’s Encephalopathy related to excessive alcohol use, thyroidtoxicosis, and septic shock.

A second key concept is that Thiamine deficiency sets up conditions in which glucose use is impaired for cellular metabolism, and administration of glucose with Thiamine deficiency can be harmful. As described below, administration of lactate and ketones appears to result in better outcomes after concussion that administration of glucose. This paper is the first to my knowledge to explain the reason for this finding. Again, there are analogous situations, described below, in which glucose without adequate Thiamine may cause injury, including Wernicke’s encephalopathy, neurodegenerative conditions, and the “Overfed Malnourished State”.

Finally, as has been well-described elsewhere, antioxidants (vitamin C and E, in particular) may be helpful in limiting oxidative damage to mitochondria during the immediate post-concussive period.

The recommendations set forth are theoretical and have not been clinically tested, therefore one should consult with a physician prior to considering any recommendations. These recommendations, which should be regularly reviewed at least monthly, include:

- Thiamine (Vitamin B1): starting dose of 100 mg 3 times a day is reasonable, followed by an increase as tolerated to 600 mg daily; maximum tolerated dose in otherwise healthy subjects in 1500 mg daily.

- Riboflavin (Vitamin B2): 400 mg daily.

- Niacinamide 100 mg 3 times a day.

- Vitamin C: 200 mg doses with Thiamine (improves thiamine absorption).

- Vitamin E (mixed tocopherol): 100 mg daily

- Magnesium: 400 mg with meals if tolerated.

Introduction

Brain concussion injury is an important medical concern with millions of people impacted yearly (Giza et al., 2013). Clinical manifestations of concussion are manifold, including amnesia, headache, fatigue, sleep disturbance, imbalance, vertigo, and eye movement impairment (Giza et al., 2013). Although most recover quickly, concussion injury may result in long-lasting functional problems, including chronic headache, memory disorders, persisting gait dysfunction, and sleep cycle disturbances (Giza et al., 2013). Management of concussion has evolved from a do-nothing approach to a protocol-driven practice involving a period of cognitive rest until asymptomatic then a gradual return of physical and cognitive exertion (Giza et al., 2013) (Makdissi et al., 2014). With this approach, most patients with a concussion will improve and be fully functional within 7 days, whereas others may require longer periods of recovery; more than 90% will fully recover within 3 weeks (McCrea et al., 2003) (Eisenberg and Mannix, 2018) (Vagnozzi et al., 2008).

Interventions are sought to increase the speed of recovery after a concussion or to prevent its long-term sequela. Dysfunction in neuronal mitochondria after trauma is an important area of focus for interventions. In this paper, we will examine nutritional interventions targeting specific pathophysiological dysfunction in neuronal mitochondria after concussion injury.

Physiological and Metabolic disruptions after a concussion

The pathophysiology of cerebral concussion is complex (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011). A traumatic impact that does not cause markedly prolonged loss of consciousness, or that does not result in intracranial hemorrhage or cranial fracture is called a mild traumatic brain injury, or concussion (Makdissi et al., 2014). In such an injury, the brain is mechanically compressed against the hard skull causing neurons of the outermost part of the brain, the cortex, to become chemically and metabolically disrupted (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011). The impacted neurons release excitary substances (such as glutamate) that alert widespread areas of the brain to the trauma (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011). Such widespread excitatory activity in the brain is pathologically similar to phenomenon seen in conditions like epilepsy, migraine, or stroke (Ellis et al., 2017) (Hishaw, 2012) (Yang et al., 2018). Overstimulation of this kind after concussion first causes an extreme hypermetabolic state lasting for several hours followed by marked depletion of brain energy for days to weeks. The main fuel for the brain, glucose, is used rapidly during the early hypermetabolic stage (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011).

In normal circumstances, glucose is metabolized by brain cells during glycolysis where a keto-acid called pyruvate is formed (Gropper et al., 2013). Using pyruvate, the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDC) enzyme facilitates a key reaction that accomplishes 3 tasks (Gropper et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2009) that are important to understand for the proposed nutritional intervention:

- (Veselá and Wilhelm, 2002) (Baev et al., 1995) (Kogan et al., 1996). CO2 also acts as a vasodilator maintaining cerebral blood flow in normal conditions. Reduced CO2 concentration leads to vasoconstriction and decreased oxygen delivery (Fathi et al., 2011).

This important enzyme, PDC, will not function properly without thiamine (vitamin B1), niacin (vitamin B3, the source of NAD+), riboflavin (Vitamin B2), pantothenic acid, and magnesium (Gropper et al., 2013). All of these are important elements of the nutritional intervention proposed here.

Immediately following a concussion, the rapid use of glucose leads to elevated demands on the PDC and the mitochondria which consume vital nutrients and creates oxidative stress (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011). When the PDC is unable to function due to a lack of supporting nutrients, pyruvate cannot be used for ATP in the mitochondria, and instead must be converted to lactic acid (Carpenter et al., 2015) (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Gropper et al., 2013).

Simultaneously, in the mitochondria, where high-energy ATP molecules are being made at extreme rates, oxygen radicals develop (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011). Normally, these radicals are quenched by antioxidants such as vitamin C and E, glutathione reductases, and CO2 (Gropper et al., 2013) (Veselá and Wilhelm, 2002). However, antioxidants also become depleted resulting in mitochondrial structure damage(Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Signoretti et al., 2011).

NADH accumulates in the hypermetabolic state and the cell takes on a reduced state (Yang, Y. and Sauve, A.A. (2016), Williamson, J.R. et al. (1993)). The reduced state can also be seen with low oxygen supply however since oxygen is not lacking after concussion this state after concussion is called “pseudohypoxia” (Williamson, J.R. et al. (1993)). The cell then “reduces” pyruvate to form lactic acid, an emergency pathways for ATP production(Yang, Y. and Sauve, A.A. (2016)). Additionally, lactate activates NMDA receptors (reducing the thiol group) which further adds to the brain excitatation by releasing glutamate. (Krasnow, A.M. and Attwell, D. (2016)).

Alternative energy is also produced via the breakdown of protein and lipids (ketones, fatty acids) (Giza and Hovda, 2001) (Gropper et al., 2013) (Signoretti et al., 2011). The cumulative damage to normal metabolism creates a low metabolic state in the brain which will persist until the body can replenish supplies. At this stage, the importance of brain rest is highlighted as the brain begins the process of restocking energy and nutrients to be used to heal and re-establish normal metabolism.

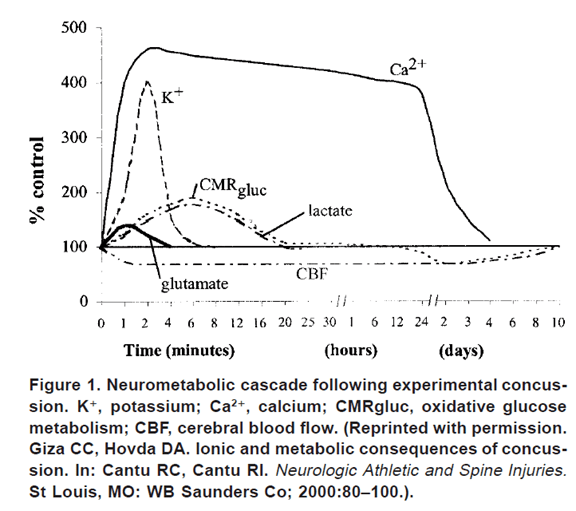

Figure 1 shows the pathophysiology of concussion visually. Minutes after a concussion the marked increase in glucose use seen (CMRgluc curve) followed by a decrease over days. The associated lactate increase is also seen. The hypermetabolic excitotoxic state is also seen with the rapid rise in glutamate.

Review of Nutritional Interventions

The proposed nutritional intervention in this paper relates to the 3 key points discussed in the section on the pathophysiology of concussion including the (1) dysfunction of the PDC and (2) mitochondrial damage due to oxidative stress. (3) reduced CO2 production.

Attempts to provide the brain with energy substrates have shown that giving lactic acid (Brooks and Martin, 2015) (Carpenter et al., 2015) and ketones (Prins, 2008) (Prins and Hovda, 2009) is supportive of brain recovery; however, giving glucose (Prins, 2008; Prins and Hovda, 2009) is not helpful. One potential reason that glucose administration is ineffective is that metabolic processes in the brain is not ready to resume normal operations, principally due to lack of supporting substances and damaged mitochondria. Metabolism is restricted to using “emergency fuels” due to impaired mitochondria and inability to oxidize pyruvate into acetyl-CoA. Supporting normal metabolism includes providing the vitamins and minerals that support the PDC and the mitochondria, thus allowing the preferred fuel, glucose, to be utilized.

Thiamine supplementation

Thiamine (vitamin B1) plays a vital role in metabolism and appears essential for normal growth and development, significantly impacting the digestive, cardiovascular, and nervous systems ((Bubko et al., 2015). The brain is highly impacted by thiamine and its supplementation in deficiency states has led to the dramatic clinical improvement, to wit, it has been called the vitamin of “the reassurance of the spirit” (Bubko et al., 2015). With no significant tissue stores of thiamine, lack of intake leads to deficiency rapidly, over days to weeks (Gropper et al., 2013). As such, there are acute (such as with alcoholics) and chronic forms (possibly related to neurodegenerative conditions such as parkinsonism and dementia) of thiamine deficiency (Bubko et al., 2015; Butterworth, 2003). Chronic forms can be seen with low thiamine combined with high carbohydrate intake which leads to metabolic dysfunction, carbohydrate intolerance, and brain disorders – a phenomenon that has been called the “overfed malnourished state” (Lonsdale, 2006; Lonsdale, 2015). In concussion, thiamine may be rapidly depleted due to the hypermetabolic state described above. Supporting the idea that thiamine can be rapidly depleted in states of hypermetabolism is found in research involving septic shock, thyrotoxicosis, and Wernicke’s Encephalopathy.

Septic shock is a state of circulatory collapse in the setting of an acute systemic infection. This state is an extreme situation of a high metabolism that uses glucose rapidly to provide energy to combat the infection. Stress on the metabolic machinery results in the functional inability of the PDC and the resulting use of lactic acid for energy. The presence of high lactic acid and low pyruvate in the blood demonstrates this change from normal metabolism to emergency metabolism. Research has shown that thiamine deficiency is found in septic shock (Mallat et al., 2016; Moskowitz et al., 2014; Woolum et al., 2018).

Thyrotoxicosis also leads to hypermetabolism and has been shown experimentally to result in thiamine deficiency and an inability for PDC to operate effectively (Williams, 1943).

Additionally, alcoholics who are malnourished with low blood sugar may develop a condition known as Wernicke’s Encephalopathy if glucose is administered before thiamine supplementation (Lonsdale, 2006). Interesting to note that Wernicke’s has a curious resemblance to symptoms in the acute post-concussion patient – amnesia, balance problems, and eye movement abnormalities (XXX). These shared clinical features suggest a common mechanism may be related to thiamine deficiency and its effects.

Although human clinical trials have not been performed in support of using thiamine in head injury, a study shows that thiamine preserved mitochondrial function in the rodent model of traumatic brain injury (Mkrtchyan et al., 2018). Thiamine supplementation does have evidence in other neurological conditions such as parkinsonism, Multiple Sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (Bubko et al., 2015; Sevim et al., 2017; Van Reeth, 1999).

Magnesium supplementation

Magnesium appears essential for thiamine to function properly (D. Lonsdale, 2015 (2). Cases of thiamine unresponsive patients have been reported associated with magnesium deficiency (Traviesa, 1974). Magnesium has shown to be essential for thiamine function as a transketolase, however, the precise role magnesium has on thiamine is unclear (Traviesa, 1974).

Magnesium is stored in the bone and inside of cells. The bone pool contains 50-60% of magnesium and is released slowly if needed as a reserve (Gropper et al., 2013), therefore bone stores are not an ideal source for brain magnesium after a concussion. Since magnesium depletion may be present, and since magnesium is essential to thiamine function, it is part of this proposed nutritional intervention. Moreover, magnesium supplementation is safe and has been shown to improve migraine symptoms which are common in concussion patients (von Luckner and Riederer, 2018). There is also research support of magnesium supplementation after concussion through a study that found that magnesium improves cognitive function after TBI in rodents (Hoane, 2007, 2005).

Riboflavin and Niacin supplementation

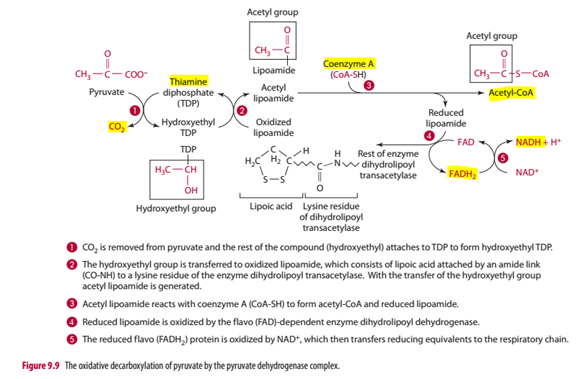

The riboflavin co-enzyme FADH2 serves as an intermediary electron carrier in the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate in the mitochondria cytosol, supporting the PDC enzyme. In the process, FADH2 carries an electron to form a niacin coenzyme, NADH, from NAD+, and converting FADH2 back to FAD. FAD is rehydrogenated in the process of pyruvate being converted to acetyl CoA. NADH is then shuttled into the mitochondrial matrix to participate in the electron transport chain which ultimately creates ATP, CO2, and H2O (Gropper et al., 2013).

The body will store Riboflavin for 2-6 weeks typically in non-brain organs (liver-kidney, heart), therefore the brain is dependent on serum riboflavin (Gropper et al., 2013). With rapid metabolism after a concussion, resupply comes from mobilized vitamins from the liver and diet. Thus, supplementing riboflavin is likely a key component to maintain PDC function after a concussion. In support of riboflavin supplementation, a study showed that riboflavin improves behavioral outcomes and edema formation after TBI (Hoane et al., 2005).

As no organ stores niacin, dietary sources are needed (colonic bacteria also may produce niacin). Additionally, the amino acid tryptophan can be converted to niacin. Nicotinamide is the precursor for NAD+ which is the active co-enzyme in the mitochondrial matrix (Gropper et al., 2013). Maintaining adequate supplies of NAD+ is vital for PDC functioning. In support of supplementing niacin, one study found that intranasal NAD supplementation prevented post-TBI neuronal death in rodents (Won et al., 2012). Additionally, supplementing before TBI improved neuronal cellular energy levels (Hüttemann et al., 2008)

Pantothenic Acid supplementation

Pantothenic acid synthesizes coenzyme A which is essential in the PDC for converting pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. There is generally a high concentration of CoA in the brain, and widely available in most commonly eaten foods (Gropper et al., 2013). Although important to PDC function, replacement of this vitamin is not likely to be of benefit as there is less likelihood of a rapid depletion present after a concussion.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) – the importance of CO2 will be discussed in another paper.

Figure 2 is a schematic showing the important elements of the PDC function including the vitamins and minerals just discussed, highlighted in yellow (Gropper et al., 2013)

Free-radical induced oxidative damage and membrane lipid peroxidation are key components to mitochondrial damage after a concussion due to the increase in oxygen metabolism in the hyperglycolysis phase described above (Giza and Hovda, 2001). Fat-soluble vitamins, C and E, have been studied and shown to be associated with improvement after a concussion (Erdman et al., 2011). Also, studies involving stroke have shown how antioxidants improve outcomes. After acute cerebral infarctions, increased consumption of the antioxidants vitamin C and E has been found (Aquilani et al., 2011). Patients with low serum vitamin C deteriorated significantly after stroke (Aquilani et al., 2011). Also, studies have found that reduced total antioxidant activity of plasma is associated with a higher volume of stroke size and degree of neurological impairment (Aquilani et al., 2011).

Vitamin C supplementation

Vitamin C in the form of ascorbic acid is an essential nutrient against oxidative stress, via its ability to donate protons to reactive oxygen species that damage cells (Gropper et al., 2013). The brain has particularly high levels of vitamin C, approximately 100 times higher than levels in most other tissues in the body (Grünewald, 1993; Rice, 2000). Depending on the pre-injury nutritional state, vitamin C may yield a significant benefit.

Vitamin E supplementation

Vitamin E in the form of alpha-tocopherol is known for its anti-oxidant properties that halts the production of ROS when fat undergoes oxidation (Gropper et al., 2013). The level of alpha-tocopherol is also high in the brain, and its concentration is normally regulated (Spector and Johanson, 2007). In support of its vitamin E’s use as a supplement after a concussion, rodent studies have shown a reduction in oxidized proteins, improvement in cognitive function, and decreased lipid peroxidation. No human studies have been performed in TBI (Haar et al., 2016).

Concussion Nutritional Intervention

Based on the discussion above, this proposal will focus on nutritional elements specifically targeting the PDC enzyme and oxidative stress in the mitochondria, including B vitamins, anti-oxidant fat-soluble vitamins, and magnesium. This review is not comprehensive for all components of a healthy metabolism, including thyroid function, other vitamins and minerals, and protection against other hormones that may be involved with systemic stress (such as cortisol or estrogen). Other vitamins and minerals that are reasonable to consider supplementing on a case by case basis, include vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin K, vitamin B6/9/12, zinc, copper, and calcium.

As brain chemistry is difficult to assess, biochemical assessments are a rough if not inadequate estimate of vitamin and mineral function in the brain. As such, the biochemical assessment is performed primarily to ensure that another condition is not present and needs supportive management (such as an unexpected vitamin B12 deficiency). Suggested biochemical assessment with clinical explanations are as following:

- complete cell count, metabolic panel, and liver function tests – to rule out other medical conditions

- Lactic acid to pyruvate levels – if ratio elevated, suggests thiamine deficiency and a reduced metabolic state.

- Plasma thiamine – if low, suggests thiamine deficiency

- NADH/NAD ratio in erythrocytes – if elevated, suggests niacin deficiency and a reduced metabolic state.

- The activity of FAD-dependent enzyme erythrocyte glutathione reductase – if reduced, suggests riboflavin deficiency

- Urinary pantothenic acid – if low, suggest pantothenic acid deficiency.

- Urinary biotin and of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid and 3-hydroxyisovaleryl carnitine, generated from altered metabolism of b-methylcrotonyl-CoA, – sensitive and early indicators of biotin deficiency

- RBC magnesium – if low, suggests magnesium deficiency

- Leukocyte vitamin C – if low, suggests vitamin C deficiency.

- Plasma vitamin E – if low, suggests vitamin E deficiency

Proposed intervention

Thiamine / vitamin B1

The Thiamine / vitamin B1 recommended dose for treating Wernicke’s Encephalopathy is much higher than the RDA which is 2mg, using doses >500 mg (Nishimoto et al., 2017). High-dose thiamine is well tolerated up to 1500 mg a day in healthy subjects (Smithline et al., 2012). With no TUL (PDR.net), a starting dose of 100 mg 2 times a day is reasonable, followed by an increase as tolerated to 600 mg daily.

Side effectis: allergic reaction, GI bleeding, pruritis, restlessness, diaphoresis, sneezing, nausea, weakness (PDR.net)

Contraindications: none, use caution in pregnancy and breastfeeding (PDR.net).

Interactions: none (PDR.net).

Riboflavin / vitamin B2

The Daily RDA for Riboflavin / vitamin B2 is 1.3 mg a day for adult males (NIH Fact Sheet: Riboflavin). Riboflavin has been studied and effective for migraine treatment, and doses were 400 mg of riboflavin daily (Boehnke et al., 2004).

Side effects: no significant known adverse events, use caution over 400 mg a day although no tolerable upper limit established (NIH Fact Sheet: Riboflavin).

Constrindications: none known (NIH Fact Sheet: Riboflavin).

Interactions: none (NIH Fact Sheet: Riboflavin).

Niacin / vitamin B3

Niacin / vitamin B3 has various nutritional forms. Nicotinic acid in supplemental amounts beyond nutritional needs can cause skin flushing, so some formulations are manufactured and labeled as prolonged, sustained, extended, or timed release to minimize this unpleasant side effect. Nicotinamide does not produce skin flushing because of its slightly different chemical structure. Niacin supplements are also available in the form of inositol hexanicotinate, and these supplements are frequently labeled as being “flush free” because they do not cause flushing. The absorption of niacin from inositol hexanicotinate varies widely but on average is 30% lower than from nicotinic acid or nicotinamide, which are almost completely absorbed. A niacin-like compound, nicotinamide riboside, is also available as a dietary supplement, but it is not marketed or labelled as a source of niacin (Forms (NIH Fact Sheet: Niacin):

Dose: for hyperlipidemia, dosing up to 6 g a day have been used. The RDA is ~15 mg equivalents of niacin a day with consideration of tryptophan intake. Pellagra is treated with 100 mg 3 times a day for 1 month (Gropper et al., 2013).

Side Effects: skin flushing, burning, itching, tingling sensations. Headache, rash, dizziness, decrease in blood pressure. Fatigue, impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, GI distress with nausea and pain. Blurred vision, macular edema. Elevated liver function tests and hepatic dysfunction (NIH Fact Sheet: Niacin).

Contraindications: liver disease, diabetes mellitus.

Interactions: Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, antidiabetic medications (NIH Fact Sheet: Niacin).

Vitamin C

Forms: Ascorbic acid. Vitamin C is problematic as it binds heavy metals. If heavy metal content can be checked generally preferable.

Dose: RDA is 75 mg for adult males. For treatment of scurvy, doses of 100-500 mg daily are used for 3 months. Reasonable to treat with 500 mg a day if tolerated (Gropper et al., 2013).

Side effects: diarrhea, nausea, abdominal cramps, GI disturbance (NIH Fact Sheet: vitamin C).

Contraindications: none known (NIH Fact Sheet: Vitamin C).

Interactions: increase absorption of Iron and thiamine (Gropper et al., 2013).

Vitamin E

Dose: RDA is 15 mg a day or 22 IU (Gropper et al., 2013). The amount of vitamin E one needs in general is related to how much PUFA one consumes: for every gram of PUFA one should consume 1-2 mg of vitamin E (Bässler, 1991). Dosing appears to be unclear, and vitamin E is one of the least toxic fat-soluble vitamins with mild GI distress coming at 200-800 mg a day with a TUL 1g a day (Gropper et al., 2013). For concussion, will recommend starting at 100 mg a day.

Side effects: may inhibit platelet aggregation and cause bleeding.

Contraindications: those with bleeding risks.

Interactions: antithrombotics medications, cholesterol lowering agents, chemotherapy (NIH Fact Sheet: Vitamin E).

Magnesium

The recommended form of magnesium is in the “aspartate, citrate, lactate, and chloride forms is absorbed more completely and is more bioavailable than magnesium oxide and magnesium sulfate” (NIH Fact Sheet: Magnesium).

Dose: Research in prevention of migraine suggests that 400 mg 3 times a day is reasonable if tolerated (Nattagh-Eshtivani et al., 2018).

Side Effects: gastrointestinal distress, including abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea. Cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, fatality.

Contraindications: renal disease.

Interactions: bisphosphonates, antibiotics, diuretics, proton pump inhibitors (NIH Fact Sheet: Magnesium).

Nutritional Intervention Proposal Prescription: – prescribed vitamins and minerals, and dose

Based on above information, the following prescription given to the patient if no contraindications or problematic interactions identified, and assuming biochemical analysis was unremarkable:

Daily take the following:

- Thiamine: 100 mg tablets

- On day 1: 1 tablet 2 times a day (total 200 mg)

- On day 2: 2 tablet 2 times a day (total 400 mg)

- On day 3: 3 tablets 2 times a day (total 600 mg)

- Continue 3 tablets 2 times a day

- Provide warning regarding thiamine side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

- Riboflavin: 100 mg tablets:

- 4 tablets once a day (total 400 mg)

- Provide warning regarding riboflavin side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

- Niacin-amide: 100 mg tablets

- 1 tablet 3 times a day (total 300 mg)

- Provide warning regarding riboflavin side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

- Vitamin C: 500 mg tablets

- 1 tablet once a day (500 mg total)

- Provide warning regarding vitamin C side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

- Vitamin E: 100 mg tablets

- 1 tablet once a day (100 mg total)

- Provide warning regarding vitamin E side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

- Magnesium: 400 mg tablets

- 1 tablet 3 times a day (total 1200 mg)

- Provide warning regarding magnesium side effects (see above) and instructions to call if side effects occur

The above treatment plan is in addition to normal nutritional intake with appropriate proportions of macro and micro nutrients

Follow-up Care/Testing Recommendations & Outcome Measure

Follow-up scheduled bi-weekly with symptoms checklist surveillance. Upon remission of symptoms, protocol above continued for 1 week then discontinued with taper with close monitoring of return of symptoms. Expectations are that 90% of concussed patients without treatment will be improved by 3 weeks (Vagnozzi et al., 2008).

Sources Cited:

Aquilani, R., Sessarego, P., Iadarola, P., Barbieri, A., Boschi, F., 2011. Nutrition for Brain Recovery After Ischemic Stroke: An Added Value to Rehabilitation. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 26, 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533611405793

Baev, V.I., Vasil’eva, I.V., L’vov, S.N., Shugaleĭ, I.V., 1995. [The unknown physiological role of carbon dioxide]. Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova 81, 47–52.

Bässler, K.H., 1991. On the problematic nature of vitamin E requirements: net vitamin E. Z Ernahrungswiss 30, 174–180.

Boehnke, C., Reuter, U., Flach, U., Schuh-Hofer, S., Einhaupl, K.M., Arnold, G., 2004. High-dose riboflavin treatment is efficacious in migraine prophylaxis: an open study in a tertiary care centre. European Journal of Neurology 11, 475–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00813.x

Brooks, G.A., Martin, N.A., 2015. Cerebral metabolism following traumatic brain injury: new discoveries with implications for treatment. Front. Neurosci. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00408

Bubko, I., Gruber, B.M., Anuszewska, E.L., 2015. [The role of thiamine in neurodegenerative diseases]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 69, 1096–1106.

Butterworth, R.F., 2003. Thiamin deficiency and brain disorders. Nutr Res Rev 16, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1079/NRR200367

Carpenter, K.L.H., Jalloh, I., Hutchinson, P.J., 2015. Glycolysis and the significance of lactate in traumatic brain injury. Front Neurosci 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00112

Eisenberg, M., Mannix, R., 2018. Acute concussion: making the diagnosis and state of the art management. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 30, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000620

Ellis, M.J., Cordingley, D., Girardin, R., Ritchie, L., Johnston, J., 2017. Migraine with Aura or Sports-Related Concussion: Case Report, Pathophysiology, and Multidisciplinary Approach to Management. Current Sports Medicine Reports 16, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000323

Erdman, J., Oria, M., Pillsbury, L. (Eds.), 2011. Nutrition and Traumatic Brain Injury. Improving Acute and Subacute Health Outcomes in Military Personnel. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Nutrition, Trauma, and the Brain, Washington (DC).

Giza, C.C., Hovda, D.A., 2001. The Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion. J Athl Train 36, 228–235.

Giza, C.C., Kutcher, J.S., Ashwal, S., Barth, J., Getchius, T.S.D., Gioia, G.A., Gronseth, G.S., Guskiewicz, K., Mandel, S., Manley, G., McKeag, D.B., Thurman, D.J., Zafonte, R., 2013. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: Evaluation and management of concussion in sports: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 80, 2250–2257. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd

Gropper, S., Smith, J., Carr, T., 2013. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism., 7th ed. Cengage Learning.

Grünewald, R.A., 1993. Ascorbic acid in the brain. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 18, 123–133.

Hishaw, A., 2012. Practical Neurology – Concussion and Epilepsy: What is the Link? [WWW Document]. Practical Neurology. URL http://practicalneurology.com/2012/06/concussion-and-epilepsy-what-is-the-link/ (accessed 1.20.19).

Haar, C.V., Peterson, T.C., Martens, K.M., Hoane, M.R., 2016. Vitamins and Nutrients as Primary Treatments in Experimental Brain Injury: Clinical Implications for Nutraceutical Therapies. Brain Res 1640, 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.030

Hoane, M.R., 2005. Treatment with magnesium improves reference memory but not working memory while reducing GFAP expression following traumatic brain injury. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 23, 67–77.

Hoane, M.R., Wolyniak, J.G., Akstulewicz, S.L., 2005. Administration of Riboflavin Improves Behavioral Outcome and Reduces Edema Formation and Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Expression after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 22, 1112–1122. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2005.22.1112

Hoane, M.R., 2007. Assessment of cognitive function following magnesium therapy in the traumatically injured brain. Magnes Res 20, 229–236.

Hüttemann, M., Lee, I., Kreipke, C.W., Petrov, T., 2008. Suppression of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase prior to traumatic brain injury improves cytochrome c oxidase activity and normalizes cellular energy levels. Neuroscience 151, 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.029

Kogan, A.K., Grachev, S.V., Eliseeva, S.V., Bolevich, S., 1996. [Ability of carbon dioxide to inhibit generation of superoxide anion radical in cells and its biomedical role]. Vopr. Med. Khim. 42, 193–202.

Krasnow, A.M. and Attwell, D. (2016) ‘NMDA Receptors: Power Switches for Oligodendrocytes’, Neuron, 91(1), pp. 3–5. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.023.

Lonsdale, D., 2006. A review of the biochemistry, metabolism and clinical benefits of thiamin(e) and its derivatives. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 3, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nek009

Lonsdale, D., 2015. The Role of Thiamin in High Calorie Malnutrition. jJurnal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 3, 1061.

Lonsdale, D., 2015 (2). Thiamine and magnesium deficiencies: keys to disease. Med. Hypotheses 84, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2014.12.004

Makdissi, M., Davis, G., McCrory, P., 2014. Updated guidelines for the management of sports-related concussion in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 43, 94–99.

Mallat, J., Lemyze, M., Thevenin, D., 2016. Do not forget to give thiamine to your septic shock patient! Journal of Thoracic Disease 8, 1062–1066. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2016.04.32

McCrea, M., Guskiewicz, K.M., Marshall, S.W., Barr, W., Randolph, C., Cantu, R.C., Onate, J.A., Yang, J., Kelly, J.P., 2003. Acute Effects and Recovery Time Following Concussion in Collegiate Football Players: The NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA 290, 2556. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.19.2556

Mkrtchyan, G.V., Üçal, M., Müllebner, A., Dumitrescu, S., Kames, M., Moldzio, R., Molcanyi, M., Schaefer, S., Weidinger, A., Schaefer, U., Hescheler, J., Duvigneau, J.C., Redl, H., Bunik, V.I., Kozlov, A.V., 2018. Thiamine preserves mitochondrial function in a rat model of traumatic brain injury, preventing inactivation of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics 1859, 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.005

Moskowitz, A., Graver, A., Giberson, T., Berg, K., Liu, X., Uber, A., Gautam, S., Donnino, M.W., 2014. The relationship between lactate and thiamine levels in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Journal of Critical Care 29, 182.e5-182.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.008

Nattagh-Eshtivani, E., Sani, M.A., Dahri, M., Ghalichi, F., Ghavami, A., Arjang, P., Tarighat-Esfanjani, A., 2018. The role of nutrients in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraine headaches: Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 102, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.059

Nishimoto, A., Usery, J., Winton, J.C., Twilla, J., 2017. High-dose Parenteral Thiamine in Treatment of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy: Case Series and Review of the Literature. In Vivo 31, 121–124. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.11034

Prins, M., 2008. Diet, ketones, and neurotrauma. Epilepsia 49, 111–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01852.x

Prins, M.L., Hovda, D.A., 2009. The Effects of Age and Ketogenic Diet on Local Cerebral Metabolic Rates of Glucose after Controlled Cortical Impact Injury in Rats. Journal of Neurotrauma 26, 1083–1093. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2008.0769

Rice, M.E., 2000. Ascorbate regulation and its neuroprotective role in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 23, 209–216.

Sharma, P., Benford, B., Li, Z.Z., Ling, G.S., 2009. Role of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in traumatic brain injury and Measurement of pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme by dipstick test. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.50739

Signoretti, S., Lazzarino, G., Tavazzi, B., Vagnozzi, R., 2011. The Pathophysiology of Concussion. PM&R 3, S359–S368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.07.018

Smithline, H.A., Donnino, M., Greenblatt, D.J., 2012. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose oral thiamine hydrochloride in healthy subjects. BMC Clinical Pharmacology 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6904-12-4

Spector, R., Johanson, C.E., 2007. REVIEW: Vitamin transport and homeostasis in mammalian brain: focus on Vitamins B and E: Vitamin transport and homeostasis in mammalian brain. Journal of Neurochemistry 103, 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04773.x

Traviesa, D.C., 1974. Magnesium deficiency: a possible cause of thiamine refractoriness in Wernicke-Korsakoff encephalopathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 37, 959–962.

Vagnozzi, R., Signoretti, S., Tavazzi, B., Floris, R., Ludovici, A., Marziali, S., Tarascio, G., Amorini, A.M., Di Pietro, V., Delfini, R., Lazzarino, G., 2008. TEMPORAL WINDOW OF METABOLIC BRAIN VULNERABILITY TO CONCUSSION: A PILOT 1H-MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPIC STUDY IN CONCUSSED ATHLETES—PART III. Neurosurgery 62, 1286–1296. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000333300.34189.74

Veselá, A., Wilhelm, J., 2002. The role of carbon dioxide in free radical reactions of the organism. Physiol Res 51, 335–339.

von Luckner, A., Riederer, F., 2018. Magnesium in Migraine Prophylaxis-Is There an Evidence-Based Rationale? A Systematic Review. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 58, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13217

Williams, R.H., 1943. ALTERATIONS IN BIOLOGIC OXIDATION IN THYROTOXICOSIS: I. THIAMINE METABOLISM. Archives of Internal Medicine 72, 353. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1943.00210090054005

Williamson, J.R. et al. (1993) ‘Hyperglycemic Pseudohypoxia and Diabetic Complications’, Diabetes, 42(6), pp. 801–813. doi:10.2337/diab.42.6.801.

Woolum, J.A., Abner, E.L., Kelly, A., Thompson Bastin, M.L., Morris, P.E., Flannery, A.H., 2018. Effect of Thiamine Administration on Lactate Clearance and Mortality in Patients With Septic Shock*: Critical Care Medicine 46, 1747–1752. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003311

Won, S.J., Choi, B.Y., Yoo, B.H., Sohn, M., Ying, W., Swanson, R.A., Suh, S.W., 2012. Prevention of Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Neuron Death by Intranasal Delivery of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide. Journal of Neurotrauma 29, 1401–1409. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.2228

Yang, J.-L., Mukda, S., Chen, S.-D., 2018. Diverse roles of mitochondria in ischemic stroke. Redox Biol 16, 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2018.03.002

Yang, Y. and Sauve, A.A. (2016) ‘NAD(+) metabolism: Bioenergetics, signaling and manipulation for therapy’, Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta, 1864(12), pp. 1787–1800. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.06.014.

The G-Doc (c)

Leave a comment